NeuroClub : the “Brain Factory”

15 March 2019

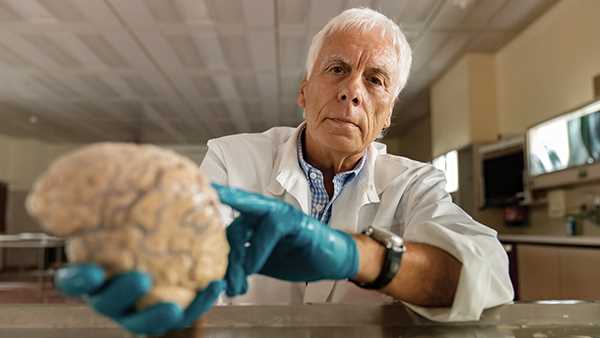

Professor Jozsef Kiss © Christian Lüscher

The University of Geneva’s NeuroClub, founded in 1999 on the fringes of the neuroanatomy course, introduces the world of research to budding doctors. It’s a club unlike any other, born out of professor Jozsef Kiss’s passion for teaching.

Generations of psychiatrists, neurologists and neurosurgeons from Geneva’s medical school have virtually all passed through the doors of the NeuroClub. More impressive still, most of the former students who have carved out a career in research have only one answer when asked what led them to take up research: NeuroClub!

The Club can be seen as the leading recruiting ground for the clinicians-scientists who are so important to Synapsy. To understand what the NeuroClub is, you need to immerse yourself in the career of its founder, professor Jozsef Kiss. The professor, who has recently retired, was a researcher in the Department of Basic Neurosciences in the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Geneva.

Interview :

Professor Kiss, you co-founded the NeuroClub 20 years ago with two medical students.

What is the Club exactly?

To put it simply, it’s a beer and crisps evening! An invited speaker talks about a scientific topic to do with the brain or NeuroClub student members present a research article in the form of a journal club. It’s designed for all medical students. Every event has between 20 and 100 participants. More officially: the NeuroClub is an undergraduate organization whose aims are to promote the formation of undergraduate students in fundamental and clinical neuroscience and to recruit talented and motivated students for the MD-PhD program in neurobiology.

So, it’s a seminar and journal club –which is quite common in the academic world.

What is it that makes the NeuroClub so popular?

Actually, there isn’t any journal club organized on the medicine course. But it’s a highly educational approach where participants can find out about research and the philosophy behind it. I suggest that the students work on an article with a clinical theme, and they have to present it beforehand in my office. I play at ‘deconstructing’ the presentation so they can incorporate the researchers’ approach better and think like them. The idea is to create a real-life experience, a feeling, around the meeting so the students can enhance the presentation of the article. Thanks to the involvement of the students, the NeuroClub is like a theatre where the members are sometimes the audience, sometimes the actors.

We also invite researchers to speak, when the presentation is followed by a session on careers in research. The guest of the day serves as a template for stimulating discussion and giving advice. For instance, we talk about the ideal time to do an MD or PhD or the fact that research gives you a critical mind that is very useful for the work of a clinician.

We’ve got carte blanche, really! When someone who specializes in taste is asked to give a talk, we invite a sommelier to do a wine tasting. The NeuroClub is mix of pleasure and serious experimentation: the debates are a very intense experience for participants that stays with them for life.

Why did you create the Club?

For three reasons. Firstly, the NeuroClub stands outside the standard curriculum; it doesn’t ask for or receive any financial contribution from the faculty. Its roots are exclusively in the neuroanatomy course. It’s a difficult area of expertise that makes great demands on students. Since they put so much work in, some students don’t want to let the subject drop. So, I designed something that wouldn’t simply leave them to their own devices once the course was over. Also, I’ve noticed over the years that the majority of future doctors don’t know much about the world of research. The NeuroClub gives students the chance to meet researchers and catalyze their careers. The final reason comes from my personal reflections about my role as a teacher. I think that a good teacher is someone who stays after class, someone who makes themselves available to students.

Could you say a little bit more about your approach to neuroanatomy?

I’m a neuroscientist who came from the world of medicine. I trained at the Semmelweis Medical School in Hungary in the 1970s. I was lucky enough to take the courses of very charismatic professors, Miklos Palkovits and János Szentágothai, neuroanatomists with an international reputation. Their classes were captivating and they helped nurture my romantic dream: to find the secret of life through the brain. When I came to Geneva as a researcher after a stint at NIH, I was assigned to teach neuroanatomy. I was inspired by my experiences in Hungary and I kind of made sure that the discipline was revived.

What did you revolutionize?

I try to make things appealing to the students and to enthuse them. The innovative part is teaching them how to navigate through the brain so they can construct a three-dimensional representation. Then I encourage them to use this to solve a clinical problem. I teach a method of learning that’s based on practice and the ability to think, and I ban rote learning. Doctors are like mechanics who work on humans instead of cars: they need practical work so they can gain experience. That’s why I make them handle real brains and teach them respect for the donor. In addition, I deliberately put them under stress with questions to create a real-life experience and to prepare them as best as possible for the exam. It is a very demanding oral exam where logical thought is the priority. Medicine is an art where the ability to hypothesize – rather than cramming your head full of facts – is of vital importance.

Students love and dread the course in equal measure. It’s true that it needs two months of major effort in the third year, but year after year it receives the highest ratings from the students.

Now that you are retired, who will take over?

I trained colleagues who are neuroscientists, Charles Quairiaux, Alan Carleton and Anthony Holtmaat, in neuroanatomy for years. For the NeuroClub, if I’m not there, nothing will happen. Ideally, we need a doctor but I’m still looking for one. For as long as I’m in good health, I’ll carry on because I don’t want to leave things in a mess after I’ve gone.

Check the NeuroClub on their Facebook page >

Author : Yann Bernardinelli, les Mots de la Science